How do you change someone’s mind if you think you are right and they are wrong? Psychology reveals the last thing to do is the tactic we usually resort to.

You are, I'm afraid to say, mistaken. The position you are taking makes no logical sense. Just listen up and I'll be more than happy to elaborate on the many, many reasons why I'm right and you are wrong. Are you feeling ready to be convinced?

Whether the subject is climate change, the Middle East or forthcoming holiday plans, this is the approach many of us adopt when we try to convince others to change their minds. It's also an approach that, more often than not, leads to the person on the receiving end hardening their existing position. Fortunately research suggests there is a better way – one that involves more listening, and less trying to bludgeon your opponent into submission.

A little over a decade ago Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil from Yale University suggested that in many instances people believe they understand how something works when in fact their understanding is superficial at best. They called this phenomenon "the illusion of explanatory depth". They began by asking their study participants to rate how well they understood how things like flushing toilets, car speedometers and sewing machines worked, before asking them to explain what they understood and then answer questions on it. The effect they revealed was that, on average, people in the experiment rated their understanding as much worse after it had been put to the test.

What happens, argued the researchers, is that we mistake our familiarity with these things for the belief that we have a detailed understanding of how they work. Usually, nobody tests us and if we have any questions about them we can just take a look. Psychologists call this idea that humans have a tendency to take mental short cuts when making decisions or assessments the "cognitive miser" theory.

Why would we bother expending the effort to really understand things when we can get by without doing so? The interesting thing is that we manage to hide from ourselves exactly how shallow our understanding is.

It's a phenomenon that will be familiar to anyone who has ever had to teach something. Usually, it only takes the first moments when you start to rehearse what you'll say to explain a topic, or worse, the first student question, for you to realise that you don't truly understand it. All over the world, teachers say to each other "I didn't really understand this until I had to teach it". Or as researcher and inventor Mark Changizi quipped: "I find that no matter how badly I teach I still learn something".

Explain yourself

Research published last year on this illusion of understanding shows how the effect might be used to convince others they are wrong. The research team, led by Philip Fernbach, of the University of Colorado, reasoned that the phenomenon might hold as much for political understanding as for things like how toilets work. Perhaps, they figured, people who have strong political opinions would be more open to other viewpoints, if asked to explain exactly how they thought the policy they were advocating would bring about the effects they claimed it would.

Recruiting a sample of Americans via the internet, they polled participants on a set of contentious US policy issues, such as imposing sanctions on Iran, healthcare and approaches to carbon emissions. One group was asked to give their opinion and then provide reasons for why they held that view. This group got the opportunity to put their side of the issue, in the same way anyone in an argument or debate has a chance to argue their case.

Those in the second group did something subtly different. Rather that provide reasons, they were asked to explain how the policy they were advocating would work. They were asked to trace, step by step, from start to finish, the causal path from the policy to the effects it was supposed to have.

The results were clear. People who provided reasons remained as convinced of their positions as they had been before the experiment. Those who were asked to provide explanations softened their views, and reported a correspondingly larger drop in how they rated their understanding of the issues. People who had previously been strongly for or against carbon emissions trading, for example, tended to became more moderate – ranking themselves as less certain in their support or opposition to the policy.

So this is something worth bearing in mind next time you're trying to convince a friend that we should build more nuclear power stations, that the collapse of capitalism is inevitable, or that dinosaurs co-existed with humans 10,000 years ago. Just remember, however, there's a chance you might need to be able to explain precisely why you think you are correct. Otherwise you might end up being the one who changes their mind.

20150724

The hidden tricks of powerful persuasion

Are we always in control of our minds? As David Robson discovers, it’s surprisingly easy to plant ideas in peoples’ heads without them realising.

Are we all just puppets on a string? Most people would like to assume that they are free agents – their fate lies in their own hands. But they’d be wrong. Often, we are as helpless as a marionette, being jerked about by someone else’s subtle influence. Without even feeling the tug, we do their bidding – while believing that it was our idea all along.

“What we’re finding more and more in psychology is that lots of the decisions we make are influenced by things we are not aware of,” says Jay Olson at McGill University in Quebec, Canada – who recently created an ingenious experiment showing just how easily we are manipulated by the gentlest persuasion. The question is, can we learn to spot those tricks, and how can we use them to our own advantage?

Olson has spent a lifetime exploring the subtle ways of tricking people’s perception, and it all began with magic. “I started magic tricks when I was five and performing when I was seven,” he says.

As an undergraduate in psychology, he found the new understanding of the mind often chimed with the skills he had learnt with his hobby. “Lots of what they said about attention and memory were just what magicians had been saying in a different way,” he says.

One card trick, in particular, captured his imagination as he set about his research. It involved flicking through a deck in front of an audience member, who is asked to pick a card randomly. Unknown to the volunteer, he already worked out which card they would choose, allowing him to reach into his pocket and pluck the exact card they had named – much to the astonishment of the crowd.

The secret, apparently, is to linger on your chosen card as you riffle through the deck. (In our conversation, Olson wouldn’t divulge how he engineers that to happen, but others claim that folding the card very slightly seems to cause it to stick in sight.) Those few extra milliseconds mean that it sticks in the mind, causing the volunteer to pick it when they are pushed for a choice.

As a scientist, Olson’s first task was to formally test his success rate. He already knew he was pretty effective, but the results were truly staggering – Olson managed to direct 103 out of 105 of the participants.

Unsurprisingly, that alone has attracted a fair amount of media attention – but it was the next part of the study that was most surprising to Olson, since it shows us just how easily our mind is manipulated.

For instance, when he questioned the volunteers afterwards, he was shocked to find that 92% of the volunteers had absolutely no idea that they’d been manipulated and felt that they had been in complete control of their decisions. Even more surprisingly, a large proportion went as far as to make up imaginary reasons for their choice. “One person said ‘I chose the 10 of hearts because 10 is high number and I was thinking of hearts before the experiment started’,” says Olson – despite the fact that it was really Olson who’d made the decision. What’s more, Olson found that things like personality type didn’t seem to have much influence on how likely someone was to be influenced – we all seem equally vulnerable. Nor did the specific properties of the cards – the colour or number – seem to make success any less likely.

The implications extend far beyond the magician’s stage, and should cause us to reconsider our perceptions of personal will. Despite a strong sense of freedom, our ability to make deliberate decisions may often be an illusion. “Having a free choice is just a feeling – it isn’t linked with the decision itself,” says Olson.

Subtle menu

Don’t believe him? Consider when you go to a restaurant for a meal. Olson says you are twice as likely to choose from the very top or very bottom of the menu – because those areas first attract your eye. “But if someone asks you why did you choose the salmon, you’ll say you were hungry for salmon,” says Olson. “You won’t say it was one of the first things I looked at on the menu.” In other words, we confabulate to explain our choice, despite the fact it had already been primed by the restaurant.

Or how about the simple task of choosing wine at the supermarket? Jennifer McKendrick and colleagues at the University of Leicester found that simply playing French or German background music led people to buy wines from those regions. When asked, however, the subjects were completely oblivious to the fact.

It is less clear how this might relate to other forms of priming, a subject of long controversy. In the 2000 US election, for instance, Al Gore supporters claimed the Republicans had flashed the word “RATS” in an advert depicting the Democrat representative.

Gore’s supporters believed the (alleged) subliminal message about their candidate would sway voters. Replicating the ad with a made-up candidate, Drew Westen at Emory University, found that the flash of the word really did damage the politician’s ratings, according to subjects in the lab. Whether the strategy could have ever swayed the results of an election in the long term is debatable (similarly, the supposed success of subliminal advertising is disputed) but it seems likely that other kinds of priming do have some effect on behaviour without you realising it.

In one striking result, simply seeing a photo of an athlete winning a race significantly boosted telephone sales reps’ performance – despite the fact that most people couldn’t even remember seeing the picture. And there is some evidence showing that handing someone a hot drink can make you seem like a “warmer” person, or smelling a nasty odour can make you more morally “disgusted” and cause you to judge people more harshly.

How to spot manipulation

Clearly, this kind of knowledge could be used for coercion in the wrong hands, so it’s worth knowing how to spot others trying to bend you to their will without you realising.

Based on the scientific literature, here are four manipulative moves to watch out in your colleagues and friends in everyday life:

1) A touch can be powerful

Simply tapping someone on the shoulder, and looking them in the eye, means they are far more open to suggestion.

It’s a technique Olson uses during his trick, but it also has been shown to work in various everyday situations – such as persuading people to lend money.

2) The speed of speech matters

Olson says that magicians will often try to rush their volunteers so they choose the first thing that comes to mind – hopefully the idea that you planted there. But once they have made their choice, they switch to a more relaxed manner.

The volunteer will look back and think they had been free to make up their mind in their own time.

3) Be aware of the field-of-view

By lingering on his chosen card, Olson made it more “salient” so it stuck in the volunteers’ minds without them even realising it.

There are many ways that can done, from placing something at eye level, to moving something slightly closer to a target. For similar reasons, we often end up taking away the first thing offered to us.

4) Certain questions will plant ideas

For example, “Why do you think this would be a good idea?” or “What do you think the advantages would be?” It sounds obvious, but letting someone persuade themselves will mean they are more confident of their decision in the long term – as if it had been their idea all along.

We may all be puppets guided by subtle influences – but if you can start to recognise who’s pulling the strings, you can at least try to push back.

Are we all just puppets on a string? Most people would like to assume that they are free agents – their fate lies in their own hands. But they’d be wrong. Often, we are as helpless as a marionette, being jerked about by someone else’s subtle influence. Without even feeling the tug, we do their bidding – while believing that it was our idea all along.

“What we’re finding more and more in psychology is that lots of the decisions we make are influenced by things we are not aware of,” says Jay Olson at McGill University in Quebec, Canada – who recently created an ingenious experiment showing just how easily we are manipulated by the gentlest persuasion. The question is, can we learn to spot those tricks, and how can we use them to our own advantage?

Olson has spent a lifetime exploring the subtle ways of tricking people’s perception, and it all began with magic. “I started magic tricks when I was five and performing when I was seven,” he says.

As an undergraduate in psychology, he found the new understanding of the mind often chimed with the skills he had learnt with his hobby. “Lots of what they said about attention and memory were just what magicians had been saying in a different way,” he says.

One card trick, in particular, captured his imagination as he set about his research. It involved flicking through a deck in front of an audience member, who is asked to pick a card randomly. Unknown to the volunteer, he already worked out which card they would choose, allowing him to reach into his pocket and pluck the exact card they had named – much to the astonishment of the crowd.

The secret, apparently, is to linger on your chosen card as you riffle through the deck. (In our conversation, Olson wouldn’t divulge how he engineers that to happen, but others claim that folding the card very slightly seems to cause it to stick in sight.) Those few extra milliseconds mean that it sticks in the mind, causing the volunteer to pick it when they are pushed for a choice.

As a scientist, Olson’s first task was to formally test his success rate. He already knew he was pretty effective, but the results were truly staggering – Olson managed to direct 103 out of 105 of the participants.

Unsurprisingly, that alone has attracted a fair amount of media attention – but it was the next part of the study that was most surprising to Olson, since it shows us just how easily our mind is manipulated.

For instance, when he questioned the volunteers afterwards, he was shocked to find that 92% of the volunteers had absolutely no idea that they’d been manipulated and felt that they had been in complete control of their decisions. Even more surprisingly, a large proportion went as far as to make up imaginary reasons for their choice. “One person said ‘I chose the 10 of hearts because 10 is high number and I was thinking of hearts before the experiment started’,” says Olson – despite the fact that it was really Olson who’d made the decision. What’s more, Olson found that things like personality type didn’t seem to have much influence on how likely someone was to be influenced – we all seem equally vulnerable. Nor did the specific properties of the cards – the colour or number – seem to make success any less likely.

The implications extend far beyond the magician’s stage, and should cause us to reconsider our perceptions of personal will. Despite a strong sense of freedom, our ability to make deliberate decisions may often be an illusion. “Having a free choice is just a feeling – it isn’t linked with the decision itself,” says Olson.

Subtle menu

Don’t believe him? Consider when you go to a restaurant for a meal. Olson says you are twice as likely to choose from the very top or very bottom of the menu – because those areas first attract your eye. “But if someone asks you why did you choose the salmon, you’ll say you were hungry for salmon,” says Olson. “You won’t say it was one of the first things I looked at on the menu.” In other words, we confabulate to explain our choice, despite the fact it had already been primed by the restaurant.

Or how about the simple task of choosing wine at the supermarket? Jennifer McKendrick and colleagues at the University of Leicester found that simply playing French or German background music led people to buy wines from those regions. When asked, however, the subjects were completely oblivious to the fact.

It is less clear how this might relate to other forms of priming, a subject of long controversy. In the 2000 US election, for instance, Al Gore supporters claimed the Republicans had flashed the word “RATS” in an advert depicting the Democrat representative.

Gore’s supporters believed the (alleged) subliminal message about their candidate would sway voters. Replicating the ad with a made-up candidate, Drew Westen at Emory University, found that the flash of the word really did damage the politician’s ratings, according to subjects in the lab. Whether the strategy could have ever swayed the results of an election in the long term is debatable (similarly, the supposed success of subliminal advertising is disputed) but it seems likely that other kinds of priming do have some effect on behaviour without you realising it.

In one striking result, simply seeing a photo of an athlete winning a race significantly boosted telephone sales reps’ performance – despite the fact that most people couldn’t even remember seeing the picture. And there is some evidence showing that handing someone a hot drink can make you seem like a “warmer” person, or smelling a nasty odour can make you more morally “disgusted” and cause you to judge people more harshly.

How to spot manipulation

Clearly, this kind of knowledge could be used for coercion in the wrong hands, so it’s worth knowing how to spot others trying to bend you to their will without you realising.

Based on the scientific literature, here are four manipulative moves to watch out in your colleagues and friends in everyday life:

1) A touch can be powerful

Simply tapping someone on the shoulder, and looking them in the eye, means they are far more open to suggestion.

It’s a technique Olson uses during his trick, but it also has been shown to work in various everyday situations – such as persuading people to lend money.

2) The speed of speech matters

Olson says that magicians will often try to rush their volunteers so they choose the first thing that comes to mind – hopefully the idea that you planted there. But once they have made their choice, they switch to a more relaxed manner.

The volunteer will look back and think they had been free to make up their mind in their own time.

3) Be aware of the field-of-view

By lingering on his chosen card, Olson made it more “salient” so it stuck in the volunteers’ minds without them even realising it.

There are many ways that can done, from placing something at eye level, to moving something slightly closer to a target. For similar reasons, we often end up taking away the first thing offered to us.

4) Certain questions will plant ideas

For example, “Why do you think this would be a good idea?” or “What do you think the advantages would be?” It sounds obvious, but letting someone persuade themselves will mean they are more confident of their decision in the long term – as if it had been their idea all along.

We may all be puppets guided by subtle influences – but if you can start to recognise who’s pulling the strings, you can at least try to push back.

20150721

The Best Way to Win an Argument

You are, I'm afraid to say, mistaken. The position you are taking makes no logical sense. Just listen up and I'll be more than happy to elaborate on the many, many reasons why I'm right and you are wrong. Are you feeling ready to be convinced?

Whether the subject is climate change, the Middle East or forthcoming holiday plans, this is the approach many of us adopt when we try to convince others to change their minds. It's also an approach that, more often than not, leads to the person on the receiving end hardening their existing position. Fortunately research suggests there is a better way – one that involves more listening, and less trying to bludgeon your opponent into submission.

A little over a decade ago Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil from Yale University suggested that in many instances people believe they understand how something works when in fact their understanding is superficial at best. They called this phenomenon "the illusion of explanatory depth". They began by asking their study participants to rate how well they understood how things like flushing toilets, car speedometers and sewing machines worked, before asking them to explain what they understood and then answer questions on it. The effect they revealed was that, on average, people in the experiment rated their understanding as much worse after it had been put to the test.

What happens, argued the researchers, is that we mistake our familiarity with these things for the belief that we have a detailed understanding of how they work. Usually, nobody tests us and if we have any questions about them we can just take a look. Psychologists call this idea that humans have a tendency to take mental short cuts when making decisions or assessments the "cognitive miser" theory.

Why would we bother expending the effort to really understand things when we can get by without doing so? The interesting thing is that we manage to hide from ourselves exactly how shallow our understanding is.

It's a phenomenon that will be familiar to anyone who has ever had to teach something. Usually, it only takes the first moments when you start to rehearse what you'll say to explain a topic, or worse, the first student question, for you to realise that you don't truly understand it. All over the world, teachers say to each other "I didn't really understand this until I had to teach it". Or as researcher and inventor Mark Changizi quipped: "I find that no matter how badly I teach I still learn something".

Explain yourself

Research published last year on this illusion of understanding shows how the effect might be used to convince others they are wrong. The research team, led by Philip Fernbach, of the University of Colorado, reasoned that the phenomenon might hold as much for political understanding as for things like how toilets work. Perhaps, they figured, people who have strong political opinions would be more open to other viewpoints, if asked to explain exactly how they thought the policy they were advocating would bring about the effects they claimed it would.

Recruiting a sample of Americans via the internet, they polled participants on a set of contentious US policy issues, such as imposing sanctions on Iran, healthcare and approaches to carbon emissions. One group was asked to give their opinion and then provide reasons for why they held that view. This group got the opportunity to put their side of the issue, in the same way anyone in an argument or debate has a chance to argue their case.

Those in the second group did something subtly different. Rather that provide reasons, they were asked to explain how the policy they were advocating would work. They were asked to trace, step by step, from start to finish, the causal path from the policy to the effects it was supposed to have.

The results were clear. People who provided reasons remained as convinced of their positions as they had been before the experiment. Those who were asked to provide explanations softened their views, and reported a correspondingly larger drop in how they rated their understanding of the issues. People who had previously been strongly for or against carbon emissions trading, for example, tended to became more moderate – ranking themselves as less certain in their support or opposition to the policy.

So this is something worth bearing in mind next time you're trying to convince a friend that we should build more nuclear power stations, that the collapse of capitalism is inevitable, or that dinosaurs co-existed with humans 10,000 years ago. Just remember, however, there's a chance you might need to be able to explain precisely why you think you are correct. Otherwise you might end up being the one who changes their mind.

Whether the subject is climate change, the Middle East or forthcoming holiday plans, this is the approach many of us adopt when we try to convince others to change their minds. It's also an approach that, more often than not, leads to the person on the receiving end hardening their existing position. Fortunately research suggests there is a better way – one that involves more listening, and less trying to bludgeon your opponent into submission.

A little over a decade ago Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil from Yale University suggested that in many instances people believe they understand how something works when in fact their understanding is superficial at best. They called this phenomenon "the illusion of explanatory depth". They began by asking their study participants to rate how well they understood how things like flushing toilets, car speedometers and sewing machines worked, before asking them to explain what they understood and then answer questions on it. The effect they revealed was that, on average, people in the experiment rated their understanding as much worse after it had been put to the test.

What happens, argued the researchers, is that we mistake our familiarity with these things for the belief that we have a detailed understanding of how they work. Usually, nobody tests us and if we have any questions about them we can just take a look. Psychologists call this idea that humans have a tendency to take mental short cuts when making decisions or assessments the "cognitive miser" theory.

Why would we bother expending the effort to really understand things when we can get by without doing so? The interesting thing is that we manage to hide from ourselves exactly how shallow our understanding is.

It's a phenomenon that will be familiar to anyone who has ever had to teach something. Usually, it only takes the first moments when you start to rehearse what you'll say to explain a topic, or worse, the first student question, for you to realise that you don't truly understand it. All over the world, teachers say to each other "I didn't really understand this until I had to teach it". Or as researcher and inventor Mark Changizi quipped: "I find that no matter how badly I teach I still learn something".

Explain yourself

Research published last year on this illusion of understanding shows how the effect might be used to convince others they are wrong. The research team, led by Philip Fernbach, of the University of Colorado, reasoned that the phenomenon might hold as much for political understanding as for things like how toilets work. Perhaps, they figured, people who have strong political opinions would be more open to other viewpoints, if asked to explain exactly how they thought the policy they were advocating would bring about the effects they claimed it would.

Recruiting a sample of Americans via the internet, they polled participants on a set of contentious US policy issues, such as imposing sanctions on Iran, healthcare and approaches to carbon emissions. One group was asked to give their opinion and then provide reasons for why they held that view. This group got the opportunity to put their side of the issue, in the same way anyone in an argument or debate has a chance to argue their case.

Those in the second group did something subtly different. Rather that provide reasons, they were asked to explain how the policy they were advocating would work. They were asked to trace, step by step, from start to finish, the causal path from the policy to the effects it was supposed to have.

The results were clear. People who provided reasons remained as convinced of their positions as they had been before the experiment. Those who were asked to provide explanations softened their views, and reported a correspondingly larger drop in how they rated their understanding of the issues. People who had previously been strongly for or against carbon emissions trading, for example, tended to became more moderate – ranking themselves as less certain in their support or opposition to the policy.

So this is something worth bearing in mind next time you're trying to convince a friend that we should build more nuclear power stations, that the collapse of capitalism is inevitable, or that dinosaurs co-existed with humans 10,000 years ago. Just remember, however, there's a chance you might need to be able to explain precisely why you think you are correct. Otherwise you might end up being the one who changes their mind.

20150717

People Who Curse All The Time Are Hotter, Confident And Less Stressed

The most dramatic, effective and beautiful expressions in any language come in the form of curse words.

Swearing is dramatic because it often occurs in dramatic situations that call for blunt forwardness. Curses are easily the most effective of words because there is no denying the intention of anyone using them.

When we curse, we’re usually saying exactly what is on our minds, without fear of the repercussions.

It may come off as harsh, but if there is cursing involved, the message will be read loud and clear.

But, more importantly, curse words are some of the most beautiful words that can possibly be used in daily conversation.

As a language enthusiast, I’ve spent years studying Mandarin Chinese, as well as the nuances of English and Spanish. What I’ve found is that swearing in any culture or country often conveys the highest form of passion.

I tend to curse much more than my mother thinks I should.

But you can’t blame me: I’m one of the most dedicated people I know, and when I’m invested in a project, or even just a thought or opinion, I tend to take it very seriously.

If you’re like me, then you have quite the dirty mouth. But rejoice, potty mouths: Those of us who swear by cursing have a lot more going for us than the straight-laced goody goodies.

I’m cursing my ass off because I’m confident about my sh*t, motherf*cker.

Researchers at Keele University in Staffordshire have been studying the links between cursing and mental behavior for years now, and they recently presented their information at the British Psychological Society’s annual conference.They found that cursing is most often associated with angry attitudes and emotions toward certain subjects and is used as an emotional coping mechanism.

Dr. Richard Stephens, one of the researchers for the study, tells the Daily Mail,

We want to use more taboo words when we are emotional. We grow up learning what these words are and using these words while we are emotional can help us to feel stronger.It seems as though cursing allowed the study’s participants to feel a sense of empowerment after airing out their dirty mouths.

I may have been raised somewhat unconventionally, but certain swear words in my home weren’t necessarily considered “taboo.”

But it was extremely important for my brothers and me to practice diligence with our swearing. We didn’t dare curse at our mother, and we definitely weren’t allowed to curse at our friends’ homes.

Still, if I felt extremely confident or passionate about something, I could use the occasional curse word to emphasize that.

Eventually, this escalated to me swearing at least every hour, but only in situations I feel super passionate about — which, apparently, is everything.

There’s nothing like a bad bitch with a dirty mouth.

Girls and guys alike agree: There’s nothing sexier than someone who uses words as bold and demanding of attention as they are.Not only do we feel more confident when we curse, but apparently it makes us a whole lot more attractive, too.

One survey finds that both men and women think swearing is a turn-on, but only when done in appropriate contexts.

One participant says,

Not all people can curse equally. Some people are just better equipped for it — kind of like guys wearing muscle shirts or girls bearing midriffs.What’s more interesting is that guys and girls both find members of the opposite sex even hotter when they’re swearing under the sheets.

Apparently, men find it extra attractive when a woman loses her sh*t while romping in the sack.

Makes sense, doesn’t it? There’s nothing sexier than someone who uses language the right way while having sex — because using it the wrong way is just plain creepy.

People who curse aren’t bottling up their stress and emotions.

It’s a known fact that people who vent their frustrations and explain what’s on their minds are often in healthier mental states than those who prefer to bottle up their thoughts and concerns.Think about it: Your worries and fears are like a can of soda, and by opening up that can of frustrations, you’re letting out all of the little bubbles that were consuming you. I know, a brilliant f*cking analogy.

But, by being able to truly express your genuine emotions once the feels hit you where it hurts, an immediate sense of relief comes over you.

There’s seriously no bigger stress eraser than screaming “F*CKING F*CK!” at the top of your lungs on a rooftop for the entire world to hear (trust me, I know).

When we curse, we’re not only explaining how strongly we feel in certain situations, but we’re also relieving ourselves from the stress and anger attached to that thought. By letting go of it, there is an acute therapeutic effect that definitely has a lasting impact in our mentality.

Prevention reports that by expressing our true emotions through the form of an occasional outburst or tantrum, we actually prevent our brains from releasing too much cortisol in the long run, which is the stress hormone that makes you feel all types of horrible.

So there you have it. Those of us with the dirty mouths shouldn’t be looking to clean them up too soon. Instead, swearing should come out of the taboo closet and be used by everyone on a daily basis.

If you don’t agree with me, just try channeling your inner rage regarding that assh*le at work who won’t leave you alone, the boss who you can’t stand or that paper you just can’t seem to finish. Afterward, stand on the nearest rooftop and shout every single swear in the book.

You’ll thank me when you’re done.

7 Habits Of People With Remarkable Mental Toughness

First the definition:

“The ability to work hard and respond resiliently to failure and adversity; the inner quality that enables individuals to work hard and stick to their long-term passions and goals.”

Now the word:

Grit.

The definition of grit almost perfectly describes qualities every successful person possesses, because mental toughness builds the foundations for long-term success.

For example, successful people are great at delaying gratification. Successful people are great at withstanding temptation. Successful people are great at overcoming fear in order to do what they need to do. (Of course, that doesn’t mean they aren’t scared — that does mean they’re brave. Big difference.) Successful people don’t just prioritize: They consistently keep doing what they have decided is most important.

All those qualities require mental strength and toughness — so it’s no coincidence those are some of the qualities of remarkably successful people.

Here are ways you can become mentally stronger — and as a result more successful:

The same premise applies to luck. Many people feel luck has a lot to do with success or failure. If they succeed, luck favored them, and if they fail, luck was against them.

Most successful people do sense that good luck played some role in their success. But they don’t wait for good luck or worry about bad luck. They act as if success or failure is completely within their control. If they succeed, they caused it. If they fail, they caused it.

By not wasting mental energy worrying about what might happen to you, you can put all your effort into making things happen. (And then if you get lucky, hey, you’re even better off.)

You can’t control luck, but you can definitely control you.

For some people it’s politics. For others it’s family. For others it’s global warming. Whatever it is, you care … and you want others to care.

Fine. Do what you can do: Vote. Lend a listening ear. Recycle and reduce your carbon footprint. Do what you can do. Be your own change — but don’t try to make everyone else change.

(They won’t.)

Then let it go.

Easier said than done? It depends on your perspective. When something

bad happens to you, see it as an opportunity to learn something you

didn’t know. When another person makes a mistake, don’t just learn from

it — see it as an opportunity to be kind, forgiving, and understanding.

The past is just training; it doesn’t define you. Think about what went wrong but only in terms of how you will make sure that next time you and the people around you know how to make sure it goes right.

Resentment sucks up a massive amount of mental energy — energy better applied elsewhere.

When a friend does something awesome, that doesn’t preclude you from doing something awesome. In fact where success is concerned, birds of a feather tend to flock together — so draw your unsuccessful friends even closer.

Don’t resent awesomeness. Create and celebrate awesomeness, wherever you find it, and in time you’ll find even more of it in yourself.

So if something is wrong, don’t waste time complaining. Put that mental energy into making the situation better. (Unless you want to whine about it forever, eventually you’ll have to make it better.)

So why waste time? Fix it now. Don’t talk about what’s wrong. Talk about how you’ll make things better, even if that conversation is only with yourself.

And do the same with your friends or colleagues. Don’t just serve as a shoulder they can cry on. Friends don’t let friends whine; friends help friends make their lives better.

(Sure, superficially they might seem to like you, but superficial is also insubstantial, and a relationship not based on substance is not a real relationship.)

Genuine relationships make you happier, and you’ll form genuine relationships only when you stop trying to impress and start trying to just be yourself.

And you’ll have a lot more mental energy to spend on the people who really do matter in your life.

Think about what you do have. You have a lot to be thankful for. Feels pretty good, doesn’t it?

Feeling better about yourself is the best way of all to recharge your mental batteries.

“The ability to work hard and respond resiliently to failure and adversity; the inner quality that enables individuals to work hard and stick to their long-term passions and goals.”

Now the word:

Grit.

The definition of grit almost perfectly describes qualities every successful person possesses, because mental toughness builds the foundations for long-term success.

For example, successful people are great at delaying gratification. Successful people are great at withstanding temptation. Successful people are great at overcoming fear in order to do what they need to do. (Of course, that doesn’t mean they aren’t scared — that does mean they’re brave. Big difference.) Successful people don’t just prioritize: They consistently keep doing what they have decided is most important.

All those qualities require mental strength and toughness — so it’s no coincidence those are some of the qualities of remarkably successful people.

Here are ways you can become mentally stronger — and as a result more successful:

1. Always act as if you are in total control.

There’s a saying often credited to Ignatius: “Pray as if God will take care of all; act as if all is up to you.” (Cool quote.)The same premise applies to luck. Many people feel luck has a lot to do with success or failure. If they succeed, luck favored them, and if they fail, luck was against them.

Most successful people do sense that good luck played some role in their success. But they don’t wait for good luck or worry about bad luck. They act as if success or failure is completely within their control. If they succeed, they caused it. If they fail, they caused it.

By not wasting mental energy worrying about what might happen to you, you can put all your effort into making things happen. (And then if you get lucky, hey, you’re even better off.)

You can’t control luck, but you can definitely control you.

2. Put aside things you have no ability to affect.

Mental strength is like muscle strength — no one has an unlimited supply. So why waste your power on things you can’t control?For some people it’s politics. For others it’s family. For others it’s global warming. Whatever it is, you care … and you want others to care.

Fine. Do what you can do: Vote. Lend a listening ear. Recycle and reduce your carbon footprint. Do what you can do. Be your own change — but don’t try to make everyone else change.

(They won’t.)

3. See the past as valuable training … and nothing more.

The past is valuable. Learn from your mistakes. Learn from the mistakes of others.Then let it go.

The past is just training; it doesn’t define you. Think about what went wrong but only in terms of how you will make sure that next time you and the people around you know how to make sure it goes right.

4. Celebrate the success of others.

Many people — I guarantee you know at least a few — see success as a zero-sum game: There’s only so much to go around. When someone else shines, they think that diminishes the light from their stars.Resentment sucks up a massive amount of mental energy — energy better applied elsewhere.

When a friend does something awesome, that doesn’t preclude you from doing something awesome. In fact where success is concerned, birds of a feather tend to flock together — so draw your unsuccessful friends even closer.

Don’t resent awesomeness. Create and celebrate awesomeness, wherever you find it, and in time you’ll find even more of it in yourself.

5. Never allow yourself to whine. (Or complain. Or criticize.)

Your words have power, especially over you. Whining about your problems always makes you feel worse, not better.So if something is wrong, don’t waste time complaining. Put that mental energy into making the situation better. (Unless you want to whine about it forever, eventually you’ll have to make it better.)

So why waste time? Fix it now. Don’t talk about what’s wrong. Talk about how you’ll make things better, even if that conversation is only with yourself.

And do the same with your friends or colleagues. Don’t just serve as a shoulder they can cry on. Friends don’t let friends whine; friends help friends make their lives better.

6. Focus only on impressing yourself.

No one likes you for your clothes, your car, your possessions, your title, or your accomplishments. Those are all “things.” People may like your things — but that doesn’t mean they like you.(Sure, superficially they might seem to like you, but superficial is also insubstantial, and a relationship not based on substance is not a real relationship.)

Genuine relationships make you happier, and you’ll form genuine relationships only when you stop trying to impress and start trying to just be yourself.

And you’ll have a lot more mental energy to spend on the people who really do matter in your life.

7. Count your blessings.

Take a second every night before you turn out the light and, in that moment, quit worrying about what you don’t have. Quit worrying about what others have that you don’t.Think about what you do have. You have a lot to be thankful for. Feels pretty good, doesn’t it?

Feeling better about yourself is the best way of all to recharge your mental batteries.

20150703

Minimize Obstacles First, Make Improvements Later to Stick to Habits

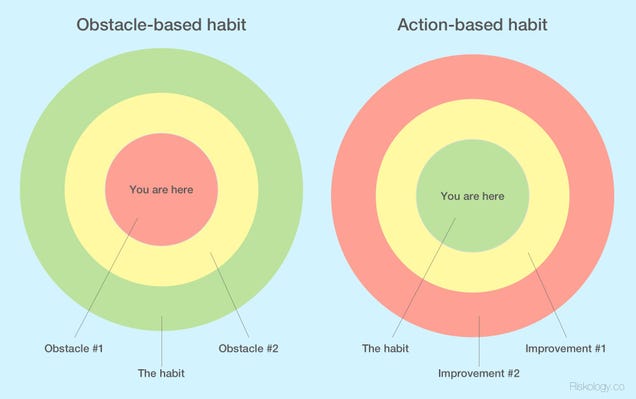

When you’re starting a new habit (or even sticking to an old one), the more things that are in your way, the more opportunities you have to break it. Rather than trying to start the habit in its best form possible, focus on removing obstacles first.

As life improvement blog Riskology points out, obstacles are the enemy of the habit. You want to start working out, but that can mean buying working out clothes (which you don’t have money for) and finding a gym (which you don’t have time for). Except, it doesn’t have to. Rather than trying to get the most optimized version of the habit right off the bat, take the minimum amount of steps necessary to get started. Once it’s a routine, you can start improving the habit as you need to:

I’m successful with my running habit (and wildly unsuccessful with others) because I’ve decided that the only thing that will stop me from getting my runs in (repetition) and improving my streak (momentum) is illness. Not waiting to get a good deal on running gear. Not feeling too busy. Not bad weather. None of these potential failure points are a part of the habit-maintenance process for me. If I’m alive and feeling at least reasonably well, I’m running on a pre-determined schedule.This might mean that your habits aren’t revolutionary changes right off the bat. If you do ten push ups every day on your lunch break, that alone probably isn’t going to get you in shape. It can, however, get you used to thinking about working out and, once you’ve got that down, you can start adding exercises, or building on your routine. The important thing is momentum.

20150702

"I’d like to raise my IQ. Where do I start?"

Dear Dumbass: I’d like to raise my IQ. Where do I start?

Do you want to raise your IQ or actually become smarter? They’re not the same thing.

IQ tests are designed to be taken cold, with no training, like the SAT (which was originally intended to be an IQ-type test). These days, of course, most people prep for the SAT, and similarly, you can get better at IQ tests by practicing.

But why would you want to? High IQ doesn’t carry much prestige. Bragging about IQ is about as likely to help someone hook up as posing with a tiger cub on Tinder.

Let’s assume you have good reason to look into this. Maybe your kid needs to hit a certain percentile on an IQ test to qualify for a gifted education program – that’s how the LA public schools do it. If so, try to find out which test your kid will be given – LA used to use Raven’s Progressive Matrices – and go online to find practice versions. Have a couple of half-hour practice sessions with your kid to familiarize her with the format and what kinds of solutions to look for. A little practice when you know what test is coming can be worth 20 IQ points.

Likewise, you can beat the SAT with many dozens of practice sessions over months and years. Instead of spending thousands of dollars on tutors, take a huge series of practice tests. The makers of the SAT used to claim that you can’t study for it, but this was based on people not studying enough. They don’t claim that anymore.

To be good at the SAT, become familiar with everything they might throw at you. This can mean going through thousands of problems. Use books of old official SATs, which you can buy on Amazon or eBay. (Unofficial SAT problems are often too slapdash to use.) Start taking practice tests early – ninth or tenth grade or even earlier. Your total score should gradually increase by hundreds of points. I know people who’ve taken 20, 30, even 80 practice tests. It’s a lot of work but effective; hardcore preppers get into kick-ass schools. Many test prep companies offer free diagnostic SATs. Or you can take a free practice PSAT, which won’t waste as much of your Saturday. The SAT has been redesigned for 2016, but most of it has stayed the same.

Back to IQ. Googling “free IQ test” returns links to more than 20 tests of varying quality. Try a few quick tests; don’t buy the deluxe diagnostics they try to sell you, and take the results with a grain of salt. Games and sites such as Brain Age, Lumosity and Big Brain Academy offer timed practice on tasks which are similar if not identical to many of the tasks used to measure IQ on professionally administered tests such as the WAIS, WISC and Stanford-Binet. If you train diligently for these tasks, your IQ scores should go up. Does this reflect a real increase in intelligence? Probably not to any great extent. Will doing leg presses every day make you a better figure skater? Maybe, but there’s so much more involved in a triple Lutz.

What if you’d like to do more than just beat IQ tests? I think you can gradually increase your actual intelligence. The primary way to do this is to get in the habit of thinking and analyzing. Most people believe they’re always thinking whenever they’re awake. But there’s a difference between thinking and perceiving. If you’re just letting life wash over you, as when you’re numbly watching Wheel of Fortune without trying to solve the puzzles, you’re not really thinking.

You may have noticed the difference in brain function between normal perception and that wrapped-in-cotton feeling you get when you’re drunk or high or exhausted. That’s kind of like the difference between active thinking and passive perceiving.

Here are some ways to nudge yourself into doing more thinking:

Do you want to raise your IQ or actually become smarter? They’re not the same thing.

IQ tests are designed to be taken cold, with no training, like the SAT (which was originally intended to be an IQ-type test). These days, of course, most people prep for the SAT, and similarly, you can get better at IQ tests by practicing.

But why would you want to? High IQ doesn’t carry much prestige. Bragging about IQ is about as likely to help someone hook up as posing with a tiger cub on Tinder.

Let’s assume you have good reason to look into this. Maybe your kid needs to hit a certain percentile on an IQ test to qualify for a gifted education program – that’s how the LA public schools do it. If so, try to find out which test your kid will be given – LA used to use Raven’s Progressive Matrices – and go online to find practice versions. Have a couple of half-hour practice sessions with your kid to familiarize her with the format and what kinds of solutions to look for. A little practice when you know what test is coming can be worth 20 IQ points.

Likewise, you can beat the SAT with many dozens of practice sessions over months and years. Instead of spending thousands of dollars on tutors, take a huge series of practice tests. The makers of the SAT used to claim that you can’t study for it, but this was based on people not studying enough. They don’t claim that anymore.

To be good at the SAT, become familiar with everything they might throw at you. This can mean going through thousands of problems. Use books of old official SATs, which you can buy on Amazon or eBay. (Unofficial SAT problems are often too slapdash to use.) Start taking practice tests early – ninth or tenth grade or even earlier. Your total score should gradually increase by hundreds of points. I know people who’ve taken 20, 30, even 80 practice tests. It’s a lot of work but effective; hardcore preppers get into kick-ass schools. Many test prep companies offer free diagnostic SATs. Or you can take a free practice PSAT, which won’t waste as much of your Saturday. The SAT has been redesigned for 2016, but most of it has stayed the same.

Back to IQ. Googling “free IQ test” returns links to more than 20 tests of varying quality. Try a few quick tests; don’t buy the deluxe diagnostics they try to sell you, and take the results with a grain of salt. Games and sites such as Brain Age, Lumosity and Big Brain Academy offer timed practice on tasks which are similar if not identical to many of the tasks used to measure IQ on professionally administered tests such as the WAIS, WISC and Stanford-Binet. If you train diligently for these tasks, your IQ scores should go up. Does this reflect a real increase in intelligence? Probably not to any great extent. Will doing leg presses every day make you a better figure skater? Maybe, but there’s so much more involved in a triple Lutz.

What if you’d like to do more than just beat IQ tests? I think you can gradually increase your actual intelligence. The primary way to do this is to get in the habit of thinking and analyzing. Most people believe they’re always thinking whenever they’re awake. But there’s a difference between thinking and perceiving. If you’re just letting life wash over you, as when you’re numbly watching Wheel of Fortune without trying to solve the puzzles, you’re not really thinking.

You may have noticed the difference in brain function between normal perception and that wrapped-in-cotton feeling you get when you’re drunk or high or exhausted. That’s kind of like the difference between active thinking and passive perceiving.

Here are some ways to nudge yourself into doing more thinking:

- Read extensively and pursue topics across multiple sources. The internet has changed how we read. We now retrieve facts quickly and narrowly, which is convenient but not sufficient for building robust thinking skills. Widen your pursuit of information. Read the entire Wikipedia article. Click on some of the links. Get a library card.

- Find big, tough questions that require long-term thought. What will daily life be like 50 years from now? How might we prove or disprove the existence of God? How can I become more effective in interpersonal interactions? Are people basically good? Take some aspect of your life about which you have a little curiosity, and see if you can pull some big questions out of it. Return to these questions whenever your brain isn’t otherwise occupied (during traffic jams or bad sex, for instance).

- Play “What if?” games. I like to pretend I’m Ben Franklin or F. Scott Fitzgerald or Jane Austen, suddenly experiencing the world through my senses. Each imaginary historical figure has to figure out when, where, and who their new host body is and what the world has turned into. This is weird, but so is NFL players high-stepping through tires. Hypotheticals imposed on everyday life are mental pushups.

- If you’re always on the internet or social media, look for mental challenges there. You can try tweeting. Twitter forces users to express their thoughts in 140 characters or less. Follow people who use Twitter to express actual thoughts, not just reports on moods or meals or 20%-off deals. Looking at the world and asking yourself “Is there a tweet in this?” forces you to make observations.

- Build up your analogy muscles. Geniuses and comedians and poets and pundits make connections between different areas of experience. Paul Cooijmans, who theorizes about intelligence, calls this “associative horizon.” It’s being good at saying “This is like that.”

- Be healthy. If your body works like crap, so does your brain. Exercise, get enough sleep, eat less junk. Take a baby aspirin every day. Floss. Try brain-boosting drugs if you want – the only one I know that works for sure is coffee. (Doesn’t make you smarter, just more alert.)

- Stay abreast of tech. Natural-born intelligence becomes less important as we become smarter via our devices. Future people will be smarter than us because they’ll have smarter devices. Tech enables not-so-smart people to stupidly text in the middle of crosswalks but also helps smart people get even smarter. Eventually we’ll have tech installed in our bodies, and people will brag about their machine brain/meat brain ratio. The tech-savvy will have more and more of an advantage.

- Learn to think like a genius. Instead of letting experience just flow over you, get in the habit of asking yourself “Why?” and “How?” Geniuses like to say they’re not smarter than other people, they just ask more questions and work more persistently to answer those questions. (This is the genius equivalent of supermodels saying they were ugly in middle school.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)